How Diet and Climate Change Are Connected

A contribution from the Sustainable Food Working Group of the Sustainability Advisory Board of the University of Vienna

December 2024

The physical root cause of climate change[1] are the massive emissions of greenhouse gases due to human activities. For humanity, the societal consequences of climate change[2] are particularly concerning, making it into a climate crisis. Without serious efforts, the next years and decades will bring increasingly severe heatwaves and floods, billions in infrastructure damage, loss of livelihoods, crop failures, food shortages, increased migration pressures, heightened risks of conflict and war, and growing societal instability. On the other hand, achieving the internationally set Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)[3] would allow us to preserve much and gain even more.

In Austria and many other countries, most individuals contribute to greenhouse gas emissions primarily through four main areas of daily life: heating with fossil fuels, mobility through cars and airplanes, excessive consumption, and diet. To avoid or mitigate catastrophic developments, significant changes are needed in all these areas. Ideally, this should happen at both the individual and societal levels, and through their interactions. There is much potential for a double benefit here: “The quality of life improves when we live, eat, and travel more energy-efficiently”[4], as a comprehensive meta study[5] concludes.

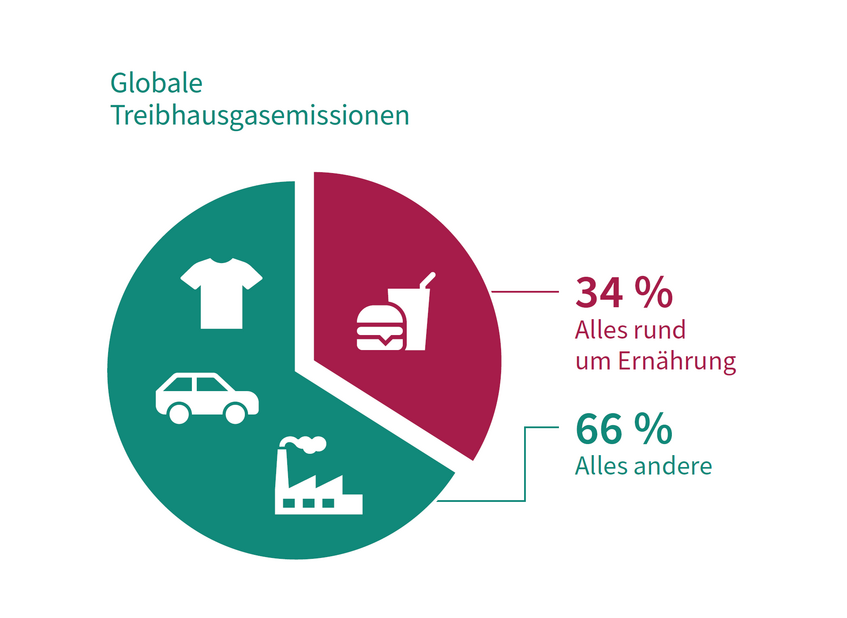

Diets play a crucial role in climate change. Globally, about one-third of all greenhouse gas emissions come from the food system[6], which includes agriculture and food production, with animal-based foods being a major driver. Other contributing factors include food waste and land-use changes such as deforestation, soil erosion, and biodiversity loss. While the global food system and its local variations are complex, the question of which areas account for the largest share of greenhouse gas emissions has a clear answer.

The food system is responsible for about one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Source: M. Crippa et al., Nature Food 2, 198-209 (2021)

Significant Differences in Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Land-Use Between Diets

Animal agriculture is many times less efficient than plant cultivation for direct human consumption. Globally, approximately 83% of all agricultural land is used for animal products[7], yet they provide only about 18% of total food calories. Conversely, crops grown for direct human consumption occupy just 17% of agricultural land but deliver 82% of all food calories. Even ”optimized” industrial animal farming consumes far more resources than it provides for humans. For example, only about 10–15% of global soybean production is consumed directly by humans[8], with the majority used as animal feed.

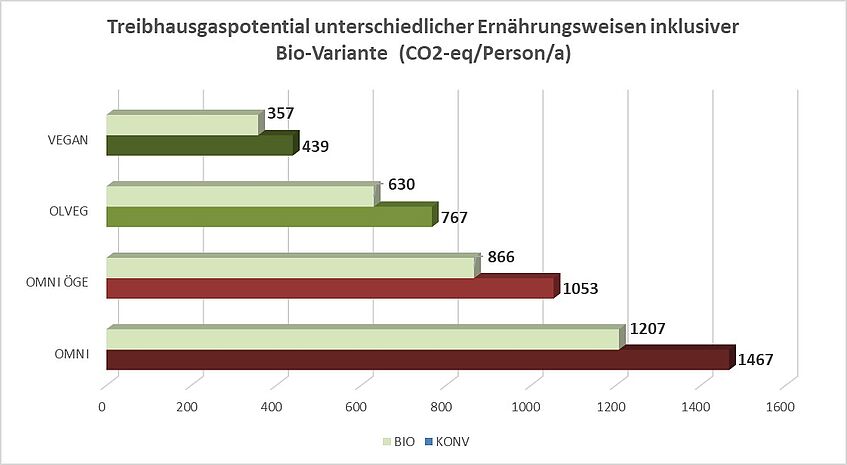

As a result, personal greenhouse gas emissions from an average omnivorous diet are significantly higher than those from a predominantly or entirely plant-based diet. In Austria, an average omnivorous diet causes twice the emissions of an average vegetarian diet and approximately four times the emissions of an average vegan diet[9]. Similar findings[10] have been reported in other European studies, which also highlight the destructive impact of omnivorous diets on land-use, eutrophication, and biodiversity loss[11]. Individual contributions can vary significantly from the average, particularly as higher consumption of meat and other animal products exacerbates the problem.

In Austria, it is often said that regional and seasonal foods contribute less to climate change. Within a given dietary choice, this is true, just as organic farming is preferable in the context of the climate crisis. However, compared to the emission differences between omnivorous and plant-based diets, these improvements are much smaller[12]. A shift to a plant-based diet is approximately an order of magnitude more impactful[13] than a shift to a solely regional diet of organic products.

Beyond dietary choices, seasonality, regionality, and organic farming play a central role in broadly sustainable nutrition. Consuming seasonal and regional foods saves costs and resources in production, storage, packaging, and transport. Organic farming combines ecological, social, and health benefits, while less processed foods are more resource-efficient.

The greenhouse gas potential varies depending on dietary choices and production methods (organic/conventional).

Source: Schlatzer M. und Lindenthal, T. (2020): Einfluss von unterschiedlichen Ernährungsweisen auf Klimawandel und Flächeninanspruchnahme in Österreich und Übersee (DIETCCLU).

The Potential of Plant-Based Diets and the Role of Universities

A global shift to a plant-based food system would result in annual emissions reductions of eight billion tons of CO2-equivalents[14] — more than twice the total emissions of the entire EU[15]. Additionally, significant financial savings are expected: predominantly plant-based diets could reduce “hidden costs” globally by $7.5 trillion[16], especially in healthcare, for example due to a reduction of cardiovascular diseases.

Such savings could free up resources to make the food system more resilient and affordable. Another positive impact would be a reallocation of the more than €50 billion in annual EU agricultural subsidies. Currently, about 82% of these subsidies go to animal farming, while 84% of EU agricultural greenhouse gas emissions come from animal farming[17].

Fundamental changes are unavoidable in the face of the climate crisis. The nature of these changes will depend significantly on human decisions: whether they will occur uncontrollably, with severe societal consequences, or whether societal systems will be guided toward positive outcomes. But the window for action is closing. Universities can play a positive role in the critical area of nutrition[18]. Specifically, the University of Vienna, through its excellent research, awareness-raising, and the establishment of enjoyable, sustainable catering in cafeterias and at events, can contribute to a liveable and sustainable future.

Sources

[2] www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-working-group-ii/

[5] www.nature.com/articles/s41558-021-01219-y

[6] www.nature.com/articles/s43016-021-00225-9

[7] www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aaq0216

[8] tabledebates.org/sites/default/files/2023-08/TABLE%20Summary%20series%20-%20Soy_0.pdf

[9] www.fibl.org/de/infothek/meldung/fibl-studie-startclim

[10] www.nature.com/articles/s43016-023-00795-w

[11] www.nature.com/articles/s43016-023-00795-w

[12] ourworldindata.org/food-choice-vs-eating-local

[13] www.fibl.org/de/infothek/meldung/fibl-studie-startclim

[14] www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/4/2019/11/Figure-5.12.jpg

[15] www.umweltbundesamt.de/daten/klima/treibhausgas-emissionen-in-der-europaeischen-union

[17] www.nature.com/articles/s43016-024-00949-4.

[18] www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(23)00082-7/fulltext